In August 2021, a huge stationary fleet of tanker vessels, bulk carriers, and container ships started building up outside eastern China’s Ningbo-Zhoushan port. The reason? A dock worker had tested positive for COVID-19, and because of China’s rigorous dynamic zero-COVID policy, this meant a closure or severely limited throughput at all of the port terminals.

The shutdown of the world’s third-largest port lasted for two weeks and had a huge impact on supply chains and logistics networks crisscrossing the planet, causing retailers around the world to worry about keeping their shelves stocked. The fallout continued for many weeks after, and the maritime logjam underlined how disruptions to manufacturing and logistics in China have far-reaching ramifications for the world.

China’s zero-tolerance COVID-19 policy and the impact on local infrastructure whenever outbreaks occur has contributed to soaring shipping costs since 2020, exacerbated by the Omicron outbreak and two-month lockdown of the city of Shanghai in early 2022. All this has led businesses and governments to raise questions about the risks of being so reliant on just one country.

“The fear of overexposure of supply chains to China has picked up, especially in the West. I think this is not just about China, but a global issue because politics plays a very big role,” says Dennis Chien, a senior analyst at Hong Kong investment firm HSZ Group. “Globalization might be coming to an end with nations trying to protect themselves.”

Lessons in logistics

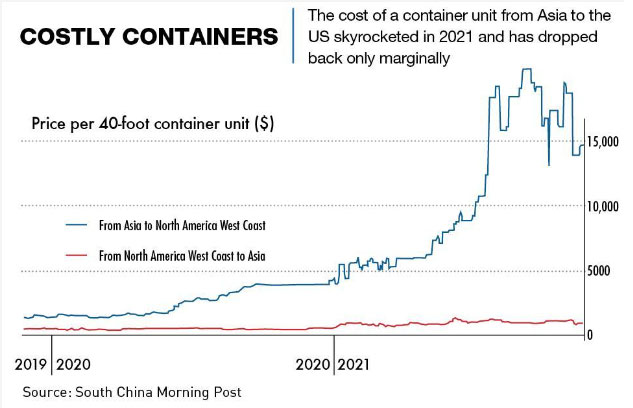

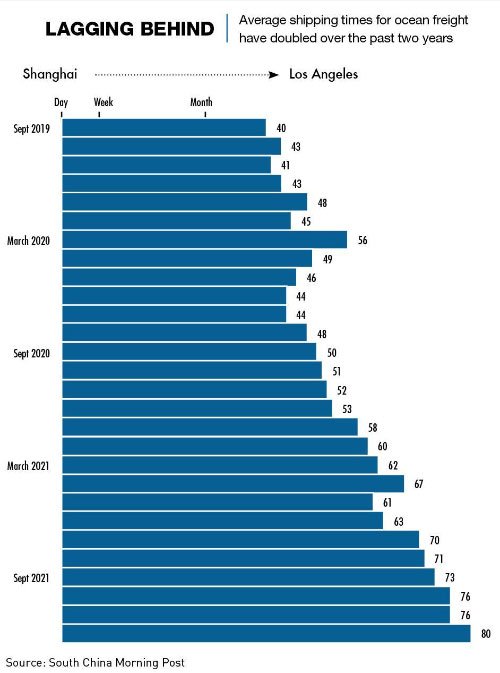

Shipping costs and cargo delays were already high entering 2022, peaking in January. And although they later fell by around 50%, the average spot freight price in the third week of March still stood at $8,832 per 40-foot container, nearly five times the $1,832 cost at the start of 2020. Average transit times for containers from China to ports in Europe have also surged, with transit time from Dalian to the British port of Felixstowe up from 65 days in January 2020 to 85 days in January 2022.

The volatility of supply chain logistics costs is giving company executives around the world sleepless nights. Nearly one-third of 130 CFOs in North America surveyed by Deloitte in the last quarter of 2021 named supply chains as their biggest external worry, and almost two-thirds believed supply chain costs would increase substantially in 2022. At the same time, the increased prices have provided a windfall for shipping companies that have benefited from the price hikes.

Chinese businesses are also facing a sizable impact from the surge in costs, according to Chien. “For Chinese companies, shipping costs have gone up by seven or eight times since before COVID-19,” he says.

China’s strict COVID policy resulted in unpredictable lockdowns, idle ports, and congested infrastructure. “There were periodic disruptions on the China side, not least when there were outbreaks and ports were shut down, particularly in Shenzhen and Shanghai,” says Ben Simpfendorfer, a Hong Kong-based partner at global management consulting firm Oliver Wyman. “For periods, that also created disruptions to shipping costs.”

But China is not entirely to blame for the increase in costs over this period. The pandemic created a global container shortage as lockdown regulations around the world stranded both staff and containers in key trade locations, leaving companies in many cases unable to operate normally.

“There is a tremendous container shortage,” says Zhou Chen, associate professor at Georgia Tech’s Stewart School of Industrial and Systems Engineering, and an expert in sustainable supply chains. “And that’s because they’re all in the wrong places.”

A labor shortage is affecting industries related to supply chains too, especially in some developed economies. Trucking companies in the US suffered a record deficit of 80,000 drivers last year, while the UK was short of more than 100,000 qualified drivers in mid-2021. The resulting slowing of inland transportation meant poor container turnover in ports across the US and the UK.

Global supply chains have also been impacted in recent years by the US-China trade war and climate-related disruptions, adding complexity to logistics networks, such as more stringent and time-consuming inspections, that have increased costs. Other events that have tested the resilience of supply chains recently include the blockage of the Suez Canal by a container ship in mid-2021, severe flooding across China, and the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

Meeting in the Middle Kingdom

By building out the world’s best logistics network of ports, railways, and telecom networks to complement its manufacturing prowess, China has entrenched itself in global supply chains on an unprecedented level. But trade rifts and also COVID-19, are forcing countries and businesses to reconsider their high dependence on China-driven supply chains. This reckoning—combined with rising labor costs in China—has encouraged companies to look at moving manufacturing elsewhere.

“What COVID-19 did is freeze the supply chain to a large degree,” says Simpfendorfer. “Before the pandemic, there was a shift taking place where manufacturers were moving into primarily either Vietnam or Mexico. In the early days of COVID-19, there was an anticipation that those flows would accelerate because of the disruption to China’s supply base. In the end, we got the reverse because the impact on the rest of the world was more significant than it was in China.”

China’s swift return to normality in 2020 after its first battle with the pandemic, reinforced its integral role in global supply chains at the time. In that year, some 30% of global trade flowed through mainland China, Hong Kong and Macao, up from 25% in 2010. China alone accounted for almost one-sixth of global goods exports—a record-high share that dwarfed the next-largest suppliers, the US and Germany.

Amid strong demand for exports, container throughput at China’s ports last year expanded by 4.5% to 4.7 billion tons, accelerating from a growth of 4% in 2020. Not content with dominating trade flows, China is increasingly controlling the infrastructure too. Three Chinese companies today monopolize global production of shipping containers, producing virtually every box in use, while China has four of the top five global container ports and seven of the top 10. Shanghai is the world’s largest port in terms of container throughput, while Ningbo-Zhoushan is the largest in terms of cargo tonnage.

Beijing has also accumulated significant ownership stakes in global ports. Chinese firms hold stakes in over a dozen European ports, with state-backed COSCO Shipping Ports purchasing a 35% stake in Hamburg’s container terminal in September 2021.

Government policy has helped Chinese companies establish a strong position in global supply chains over the past two decades and will continue to be a crucial source of support. The 14th Five-Year Plan, issued in March 2021 calls for implementing a “manufacturing great power strategy” and for policies to “guide key links in [manufacturing] industry chains to remain within China”—a clear reference to policies designed to resist pressure from Western countries for supply chain decoupling.

“The consistent thread throughout China’s economic rise has always been that the government spotlights several industries that they feel have strategic value for the long term,” says Chien. “Then they make huge investments or provide a huge incentive for private enterprise to enter. We are seeing it with manufacturing and we saw it with supply chains.”

Already home to one of the most advanced digital ecosystems in the world, China is still investing heavily in the “software” of digital infrastructure to complement its “hardware” of global physical assets. In doing so, it is looking to replicate the success of AT&T, the storied US multinational that spearheaded American dominance of global telecommunications for most of the last century.

China is working to unlock the potential of digitalized supply chains through the Digital Silk Road, which aims to link Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) countries through fiber optic cables, cellular towers, widespread internet and telecommunications connections, as well as “soft” digital infrastructure such as common technical standards, e-commerce platforms, mobile payment systems and other digital-economy applications. Chinese-owned ports around the world are prime candidates for this digitalization.

“China is investing in the future. They want to be a leader, they want to own it,” says Diane Long, managing director of Xanadu Enterprise, a strategic market entry firm for China. “The US owned the technology and infrastructure 30 years ago. They were the ones laying the undersea cables and launching satellites, but along the way, the government stopped making those investments, the in-roads, offering innovative concepts. China has replaced them.”

China’s supply high

The allure of globalization was that it promised an efficient division of labor by country. Developing economies would concentrate on the production of primary products or raw materials through low-paid labor, with the products then transported to deindustrialized economies, where other workers process, package, and market the product. But this has not materialized, as China has built robust production ecosystems for nearly every major industry.

The Middle Kingdom offers a hard-to-reproduce concentration of input suppliers, assembly factories, skilled workers and service providers—all at a massive scale and covering a broad range of low-tech, mid-tech and even high-tech products.

Over the past 20 years, profit margins in a wide range of industries and products have benefited from this concentration, according to Simpfendorfer. “It results in lower costs. Concentration allows for innovation in these clusters because you get scale.”

Higher productivity has also been the result of supply chain consolidation. “Productivity in China remains extremely high even if labor costs are not low anymore,” says Zhou. “It’s very common for businesses to be running 10-12 hours a day, six days a week. Where else could you find that? Even with higher labor costs, per unit costs remain very low because Chinese are so productive.”

Digital dividends

Beijing has made no secret of its desire for China to become a developed economy without losing its strong manufacturing export sector. With this positive outlook in mind, Chinese businesses have been willing to invest in bleeding-edge technology, such as AI and robots, to ensure their supply chain dominance endures.

Take SHEIN, China’s first global fashion giant, for example. In February, local government plans revealed the Guangzhou-based fast-fashion retailer intended to invest RMB 15 billion ($2.3 billion) to build a global supply chain center in the city this year. SHEIN boasts a unique business model that has helped it out-compete the likes of Zara and H&M—it constantly gathers and analyzes customer data and uses that knowledge to craft new designs via a vast network of small- to mid-sized workshops that bid for orders daily.

“Data assets and data management are becoming very important,” says Steven Zhong, lead partner for ESG strategy and value chain advisory at PwC China. “When we look at the more advanced digital supply chain capabilities, it’s more focused on the ability to forecast…on how you’re using historical data to forecast, and how you’re simulating different risk factors on business and sustainability impacts.”

Chinese supply chains are pushing the envelope in other ways. AI-powered robots are increasingly showing up on factory floors and in logistics warehouses, performing tasks previously handled by humans with greater efficiency than ever before. And many of these technologies are showing up in state-of-the-art factories across China that are part of the World Economic Forum’s ‘global lighthouse network’. These manufacturing sites are pioneering the adoption and integration of frontier technologies, and of the 90 “lighthouse” facilities worldwide last September, a record 28 were in China. As more of these lighthouse factories come online, China’s centrality in global supply chains is only likely to grow.

Chained up

In some ways, China has been a victim of its own success. The pandemic underlined China’s capture of supply chains and the extent to which it remains dominant even in the face of the bruising trade war with the US, forcing governments and businesses to examine their extraordinary dependence on China and the associated risks.

“If China had suffered a more serious virus outbreak, then the world would have suffered more,” says Zhou Chen. “We should be concerned about this amid a period of already-high inflation that is still rising.”

Simpfendorfer says he is worried that there will be an even greater impact on supply chains when China fully reopens its borders. “We can’t rule out the risk of potentially large disruptions, and that will have a serious impact on our ability to purchase goods and the price we pay. There is a risk that prices will rise sharply so our China exposure is a challenge.”

The strict, two-month lockdown in Shanghai, starting in late March, and a whole raft of restrictions in cities across the country caused delays that further strained global supply chains and increased costs. As the factory of the world, any disruptions to exports resulting in shortages could also drive up inflation internationally.

The relocation of manufacturing and supply chains to China in recent decades has also exacted a tremendous cost on the local environment. “There is a reason why some of the dirtiest industries are in China and not Europe or North America—they have been regulated out of business. Europeans and North Americans have to take some responsibility for that,” says Chien. Consumer demand for inexpensive goods means China’s economy has understandably gravitated toward cheaper inputs—such as dirty coal for producing low-cost electricity.

As countries reconsider whether the risks of global supply chains now outweigh the benefits, the once-unshakeable faith in globalization as a positive force and an irreversible process is now under threat with potentially seismic consequences. Unwinding decades of global economic integration has the potential to impact the free flow of goods that has underpinned growth since the Second World War.

Moving supply chains out of the world’s biggest manufacturing nation is also easier said than done, but some attractive alternatives have emerged. Southeast Asia, Vietnam in particular, has siphoned off low-end manufacturing from China in recent years, and the migration to Vietnam is expected to continue although investment slowed following the onset of COVID-19. In mid-June Apple announced for the first time that it was moving a part of its iPad manufacturing to the country.

Seeking to avoid US tariffs, Chinese factories themselves are increasingly setting up shop in Vietnam. “Chinese manufacturers tend to move as a group,” says Simpfendorfer. “Once they saw there was an ecosystem there, and that their competitors were there, then they were happier to invest in Vietnam.”

The Vietnamese are famous for their strong work ethic, a value shared with their Chinese neighbors that has helped attract factory bosses to relocate some operations across the border. But a shortage of skilled labor and problems in quality assurance remain barriers, according to PwC China’s Zhong.

The highly differentiated nature of markets in Southeast Asia can make it a headache to move sections of supply chains to the region. “China is a huge market governed by a single set of regulations across regions,” says Zhong. “You can still relocate a factory or build new distribution centers from region to region in China with attractive subsidies and support from local government, but Southeast Asia is a set of completely different markets. It’s very difficult to do the standardized model and to derive enough synergy out of the economy without evaluating pros and cons, especially risk factors on investments and cost benefits based on each country’s unique characteristics.”

Closer to home for American companies, Mexico has emerged as a strong contender as an alternative thanks to the US-China tariff war—particularly after the passage of the US-Mexico-Canada agreement in 2020. Proximity makes Mexico a tantalizing possibility for American firms because companies do not need to wait weeks for goods to be shipped from China.

Changing with the times

Geopolitical tensions that have erupted in Ukraine and global issues such as COVID are likely to have a continuing impact on the efficiency and cost of logistics networks. And China is, meanwhile, continuing to reconfigure its entire manufacturing sector, starting by de-emphasizing low-end and high-polluting production.

“The next stage will be a departure of the mid-range. Higher-end shoes or good-quality cellphones still have to be made in China as other countries are not ready,” says Zhou Chen. “But just wait—in five to 10 years, they will exit too. China will shift focus to the higher-end products.”

Another reason why China will remain the world’s manufacturing hub is that it is itself one of the world’s largest markets. This will ensure Beijing retains extensive influence over global supply chains, backed up by heavy investment in digitalization both at home and at Chinese-invested ports around the world, which puts the country in a commanding position.

“We went from a world that was relatively isolated to an interconnected one with global supply chains in China,” says Simpfendorfer. “We’re now entering the next stage of global trade where we don’t get a reversal or de-globalization, we simply get a fragmentation of the global supply chain, with China at the heart of it. [CKGSB Knowledge first published this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

The post The Truth About China and Global Supply Chains appeared first on Fair Observer.

from World News - Independent, Nonprofit Media https://ift.tt/bZtevXS https://ift.tt/x2aJTY1

0 Comments

Online Latest Bangla News, Article - Sports, Crime, Entertainment, Business, Politics, Education, Opinion, Lifestyle, Photo, Video, Travel, National, World.

Emoji